Bonds are commonly used as part of a diversified investment portfolio because they can offer security and income. Because of this, they are particularly useful for those either close to or already in retirement. But despite being such a common investment, the fancy terminology that surrounds bonds leaves many investors scratching their heads. That’s not a good position for an investor to be in, so let’s take a look at what a bond is.

The concept behind bonds is rather straight forward: bonds, which are also called fixed-interest or fixed-income securities are like big ‘IOUs’ where you are the lender. When a government or corporation need money, one option available to them is to borrow money from investors by issuing bonds. The bond is a promise for the institution to repay you the exact money you lent them as well as interest on that money, which is set at a fixed price (hence the name ‘fixed-income securities’).

The conditions of the bond are clearly set out before you make your purchase, but to understand what you’ll be investing in, you’ll need to familiarise yourself with some industry jargon.

Common terminology

- Issuer: The government or corporation issuing the bond – ie the borrower;

- Principal: How much you paid for the bond, excluding interest;

- Face Value: The principal amount invested that will be repaid on maturity;

- Maturity: The expiry date of the bond and the date you get your money back;

- Denomination: The value of one bond – bonds are usually sold in $100 units;

- Coupon: The regular interest payment for every unit – usually annualised;

- Coupon Payment Frequency: How often the interest payments are made – usually semi-annually.

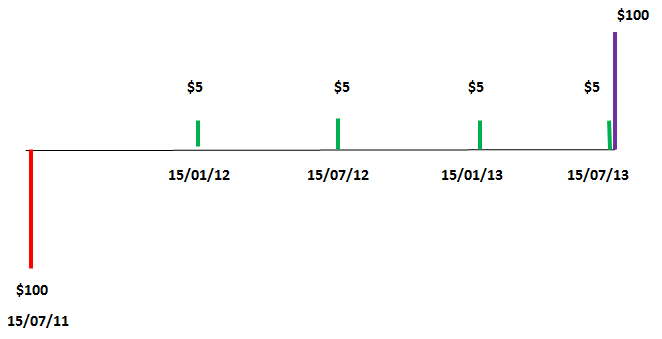

A bond can be thought of as a series of cash flows or income payments. Let’s take an example. Say you invest $100 in a two year bond that matures on July 15, 2013 (let’s pretend today is July 15, 2011). The bond has a coupon of 10% paid semi-annually. Remember, the 10% reflects the amount of interest you will receive over the entire year, which means you will actually receive two semi-annual payments equal to 5% of the $100 unit. If you hold onto that bond until maturity, the cash flows can be represented as follows:

[1]

[1]

At maturity, you will have received a total of $120.

Trading bonds

What makes bonds fun is that you don’t need to hold onto them until maturity — you can choose to trade them on the bond market. This market is also called the debt market or credit market. Once a bond enters the market, its price will change depending on demand and other influences.

Here’s some more words you will come across:

- Price: The traded price of the bond, not its original face value

- Yield: The percentage interest a bond pays when traded on the market

- Par: When a bond trades on the market at a price equal to its face value

- Premium: A bond trading above its face value

- Discount: A bond trading below its face value

The key thing to remember about traded fixed-interest securities is that the price and the yield generally move in opposite directions. Think of it as supply and demand. When demand for bonds rises, bond prices also rise. But just because you paid more for the bond, doesn’t mean the issuer is going to pay you interest on the higher price — they will continue to pay interest based on the face value of the bond. As a result, the yield is adjusted lower to indicate to the investor the new percentage return they will receive on their money.

The opposite is also true. When demand for bonds falls, prices decline. The cheaper bonds mean the original interest payment is now worth more relative to the new price paid for the bond, and so the yield will rise to reflect this.

When bonds are first issued, they are usually issued at par – that means, a $100 face value also has a traded price of $100. However, over time, economic conditions and interest rate changes will influence the demand for bonds and this will impact the price and yield.

If interest rates have fallen since the bond was issued, the price of the bond will usually trade at a premium to its face value (that is, it will be worth more than $100), since the coupon on the bond is higher than that which may be obtained in the market for newly issued bond of similar grade. Conversely, if interest rates have risen, the secondary market value of the bond will generally trade at a discount to its face value (that is, less than $100), since there is less demand for that bond because there are now other newly issued bonds on the market with higher coupons.

One major factor that drives demand for bonds is investment security. For example, when the global financial crisis hit and stock markets across the world began to nosedive, many investors moved their money into bonds for “safe parking.” This caused a greater demand for bonds that would normally be the case, and bond prices rose, pushing down yields.

Who issues bonds in Australia?

The biggest issuer of bonds is the Commonwealth Government. Also known as treasury bonds or government bonds, these are the benchmark fixed interest securities in Australia. Other bonds are generally issued at a margin to the applicable government bond interest rate (or yield). Generally, the higher the margin, the higher the perceived risk in investing in that bond (that is, the more likely that the borrower might not be able to make payments of interest or repay the principal). So called “junk” bonds are usually issued at very high margins to the underlying government bond yield, reflecting a high probability that an investor may not get their principal repaid.

Commonwealth Government bonds can be purchased from the Reserve Bank of Australia (min $1,000 face value, maximum $250,000 face value – see www.rba.gov.au [2] ), from some stockbrokers and through some specialty fixed income brokers.

The state governments also issue bonds through their borrowing agencies, such as NSW Treasury Corporation or Victoria Treasury Corporation. These bonds are more colloquially called semi-government bonds or “semis”. Some state governments offer a facility for non-institutional investors to purchase directly. Alternatively, you can usually find parcels of semi-government bonds available through selected stockbrokers and specialty fixed income brokers.

Banks and major corporations also issue bonds. Some of these bonds are targeted towards a broad group of investors including individual investors and self managed superannuation funds, and following issue, will generally be listed and quoted on the Australian Securities Exchange.

Others may only be issued to institutional investors or qualifying ‘sophisticated’ investors, and can then only be purchased in the secondary market from an investment bank or specialty fixed income dealer. For the latter, a minimum lot size of $50,000 face value or even higher will apply.

To find out about different types of bonds, including floating-rate notes and indexed bonds, read Other types of fixed income securities [3]. Or find out what calculations to use to compare different bonds in How to compare bonds [4].

Important information: This content has been prepared without taking account of the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular individual. It does not constitute formal advice. For this reason, any individual should, before acting, consider the appropriateness of the information, having regard to the individual’s objectives, financial situation and needs and, if necessary, seek appropriate professional advice.